Single-serve beverages in schools focus on healthy choices

Associations are tackling obesity through education, innovative initiatives

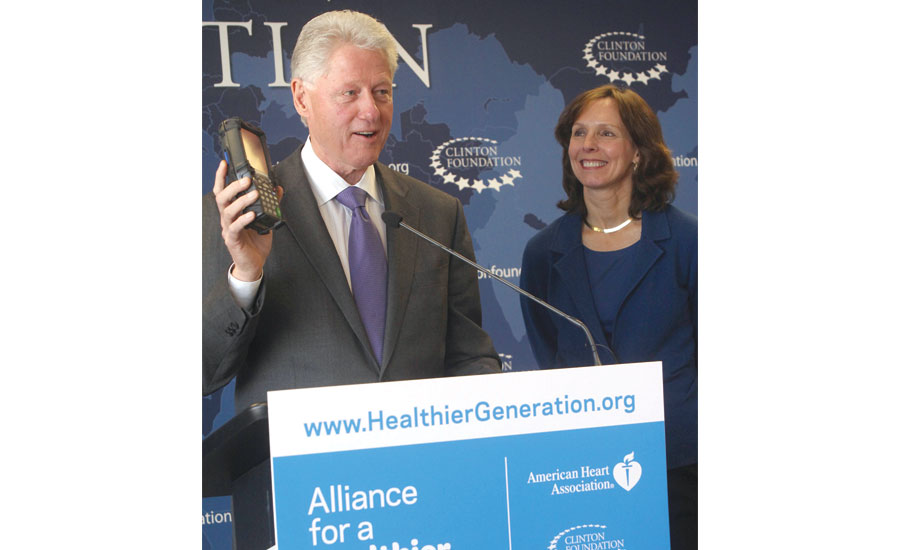

In 2010, President Bill Clinton with Susan Neely, president and chief executive officer of the American Beverage Association, announced the successful implementation of the School Beverage Guidelines. There was a 90 percent reduction of calories from beverages in grade and high schools. (Image courtesy of the American Beverage Association)

The start of the 2015-2016 school year is just around the corner, and students between the ages of five and 18 will continue to find healthier beverages and snacks in vending machines, a la carte lines and school stores due to the Smart Snacks in School regulation enacted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in July 2014.

Parents, pediatricians, member companies of the American Beverage Association (ABA), Washington, D.C., and even first lady Michelle Obama, through her Let’s Move! and Drink Up campaigns, applauded the legislation and advocated for its launch. Yet, experts say the move to fight childhood obesity and reduce the beverage calories consumed by students in schools occurred several years earlier with the 2006 development and implementation of the School Beverage Guidelines.

“Parents told us that they wanted more control over what their children and teens were drinking in schools and we listened,” says Susan Neely, president and chief executive officer at ABA. “These guidelines were the first of their kind and set the stage for the beverage component of the USDA’s regulations on what beverages can be sold in schools.

“In elementary and middle school, that meant water, milk and 100 percent juice because that is what parents told us they wanted available to their younger children,” Neely continues. “But parents wanted their teens to have more choices, so we included other options — such as diet soft drinks — all calorie capped at 66 calories per 8 ounces, limited to a 12-ounce size.”

At a 2010 press conference, the ABA, in partnership with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, a joint venture of the American Heart Association and the William J. Clinton Foundation, announced that the companies had successfully implemented the School Beverage Guidelines with positive results.

“There was a 90 percent reduction of calories from beverages in grade and high schools due to the removal of full-calorie soft drinks and replacing them with lower-calorie and smaller-portion options along with water, milk and 100 percent juice,” Neely says. She adds that public-private partnerships, the support of ABA member companies and their bottling systems, and the support of thousands of school partners all were crucial to the initiative’s success.

The data showcasing the positive results were published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2012.

Clear on Calories packaging

Packaging and labeling also has contributed to the guideline’s success, experts say. When the first lady launched Let’s Move!, the ABA also announced its Clear on Calories front-of-packaging initiative as yet another way to help consumers make informed decisions about the beverages they choose before making a purchase, Neely says. She also notes that the ABA is a partner in the Drink Up effort, a positive initiative to promote water consumption as opposed to limiting beverage options.

Additionally, new research published in the July issue of the American Journal of Public Health suggests that when bottled water is not available in vending machines, people choose other packaged beverages, which could contain sugar, caffeine and other additives.

The study titled “The Unintended Consequences of Changes in Beverage Options and the Removal of Bottled Water on a University Campus” concluded that a bottled water sales ban at the University of Vermont resulted in a 25 percent increase in the consumption of sugary drinks and an 8.5 percent increase in the amount of plastic bottles entering the waste stream, the Alexandria, Va.-based International Bottled Water Association (IBWA) said in a statement.

“The purpose of the bottled water bar sales ban was to encourage students to carry reusable water bottles that could be filled with tap water. That didn’t happen,” said Chris Hogan, vice president of communications for the IBWA, in a statement. “The study found that the increase in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption occurred even with the university’s efforts to encourage water fountain use.”

Along with the Clear on Calories packaging program, the ABA launched the Calories Count Beverage Vending program, which places calorie labels on the selection buttons of vending machines with a simple “Check then Choose” message. Last year, the ABA, in partnership with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, announced a Balance Calories Initiative, a national multi-year effort to help fight obesity by reducing beverage calories consumed by each person nationally by 20 percent by 2025.

“As an industry, we will continue to innovate on a number of fronts to bring consumers — including students — a wide range of options and the information they need to make wise choices so they can lead a healthy, balanced lifestyle,” Neely concludes.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!